Experts Corner: What Can I Use from Past Environmental Reports?

The more you know about the past, the better prepared you are for the future. Theodore Roosevelt wasn’t particularly referring to Environmental Due Diligence, but his wisdom holds true when it comes to performing high-quality environmental work.

Reviewing prior environmental reports is crucial in the due diligence process since they provide valuable insight on a property. They can reveal new issues, solve problems and list potential environmental impacts and how they may affect the project, site, and end users.

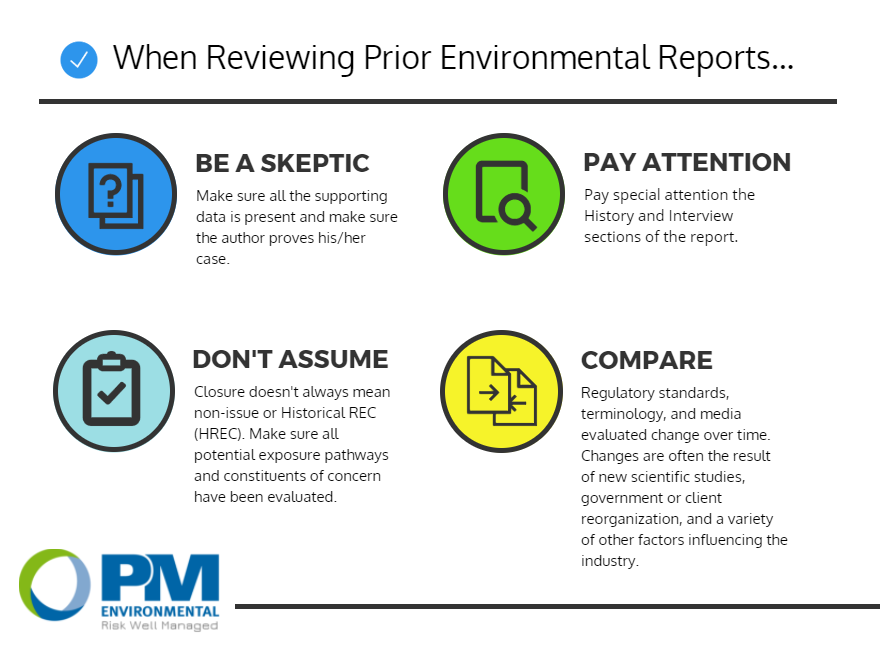

Below are a few rules of thumb when reviewing prior environmental reports.

Be a Skeptic

- Read the report with skepticism.

- Make the report author prove his/her case (i.e., data from the site meets applicable standards, there are no recognized environmental conditions, etc.)

- Make sure all the supporting data is present in the report to back up the author’s case, and that you review it to determine if you agree with the author’s conclusions.

Pay Special Attention to the History and Interview Sections of the Report

If operations at the site have significantly changed over time, the previous report can provide documentation of historic operations that might not be currently available. Interviews can be equally important.

For example, an industrial site was recently evaluated via a Phase I Environmental Site Assessment (ESA). It initially concluded that staining observed around an aboveground fuel storage area, which located outside adjacent to the building, was considered a de minimis condition.

A de minimis condition is a condition that generally does not present a threat to human health or the environment, and generally would not be the subject of an enforcement action if brought to the attention of appropriate governmental agencies.

The concrete was in good condition (i.e. no cracking or spalling) and the staining was localized. However, review of the interview section of a previous report indicated the fuel storage area was in a historically stained graveled area. It was not considered an environmental concern to the previous consultant.

This information, coupled with the knowledge of the significant length of time of fuel storage on the graveled area, elevated the concern of a potential material threat of release in this area.

Don’t Assume Closure or Historical REC (HREC) Means Non-Issue

Make sure that all the potential exposure pathways and constituents of concern (COCs) have been evaluated. Exposure pathways are routes that COCs move through the environment from a source to a point where people come in contact with the COCs.

For example, an industrial property utilized trichloroethylene (TCE) in its manufacturing process in the 1980s. When the process was altered and TCE was no longer necessary, the TCE storage area obtained regulatory closure through the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

The standards utilized at the time were direct-contact standards for TCE, which were the maximum allowable concentration for dermal contact by an adult. The vapor intrusion pathway (i.e., the migration of volatile COCs from contaminated soil and/or groundwater into indoor air spaces of occupied buildings), and the concentrations remaining in the soil indicated a potential concern for vapor intrusion. The pathway was not intentionally overlooked.

A national consensus on evaluating the vapor intrusion pathway did not exist until 2002. The issue did not re-open the regulatory closure. Therefore, the pathway required evaluation to determine if on-site employees were at risk of vapor inhalation by regulatory-allowable concentrations remaining in the contaminant source area.

Always Compare to Current Standards and Terminology

Regulatory standards, terminology, and media evaluated change over time. Changes are often the result of new scientific studies, government or client reorganization, and a variety of other factors influencing the industry.

An example of a change to all three are the target concentrations the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) uses for evaluation of contaminated properties.

In 2002, the USEPA developed the USEPA Region 9 Preliminary Remediation Goals (PRGs) as applicable standards for cleanup of soil and groundwater.

In 2008, USEPA started using Regional Screening Levels (RSLs), which are updated bi-annually (http://www.epa.gov/risk/regional-screening-levels-rsls). Each new release of RSLs are updated with new toxicity and exposure data that has been obtained from the most recent applicable studies. The USEPA uses RSLs differently from the former use of PRGs. RSLs are utilized as initial screening levels and not cleanup goals, whereas PRGs were utilized primarily as cleanup goals.

Another example of changing terminology is the accepted acronym for contaminants when released to the environment. Historically, when gasoline or other petroleum type products, were accidentally released from an underground storage tank (UST) or other structure, it was called “free product.”

Regulators and industry professionals were often unsure of the undefined term “product”, and frequently noted there was nothing “free”, literally or figuratively, about a contaminant. The terms “separate phase hydrocarbon (SPH)”, “extractable phase hydrocarbon (EPH)”, and “phase separated hydrocarbon (PSH)”, were all utilized in the early 2000s with little consensus from state to state, industry to industry, and professional to professional.

In the late 2000s, the descriptive term “non-aqueous phase liquid (NAPL)” was promoted by ITRC and USEPA and is now the standard for describing the mass of a bulk contaminant release to the environment. The term NAPL may be preceded by the descriptive prefix L, for light, or D, for dense, to describe the relative density of the NAPL with respect to water. Also, LNAPLs float, and DNAPLs sink.

The methods for how to evaluate a contaminated property have also changed over time. In the 1980s, most cleanup goals and standards were less than detection levels. In the 1990s, cleanup goals and standards evolved to allow small amounts of contaminants to remain, if the exposure risk was minimal. In the 2000s, work and research was completed to develop more accurate toxicity and exposure data to refine cleanup goals and standards.

Since 2010, the focus for cleanup goals and standards has shifted to the big picture of a contaminated site evaluation by using tools such as a Conceptual Site Model (CSM), predictive transport and exposure, and compounding effects of multiple releases, exposure pathways, and chemicals. The evaluation of compounding effects is referred to as multiple chemical adjustments (MCAs) and exposure pathway.

Standards and terminology and methods are continuously being updated and changed. Therefore, PM Environmental regularly participates in continuing education, professional development, and technical advisory groups, to ensure that PM provides the best, most up to date and relevant products to our clients.

As one can see, lots of information that can be obtained and evaluated from prior environmental reports before determining additional courses of action. However, that information should be carefully reviewed by an environmental professional with experience in dissecting historical environmental reports.

Publication Details

Date

April 15, 2016